Patience Is No Virtue for the Fed

- Patience Is No Virtue for the Fed

- ETF Talk: Tap Large-Cap Stocks with This Fund

- Breaking Up Is Hard to Do (Another Defense of ‘Economic Bigness’)

- Always Trust Your Cape

***********************************************************

Patience Is No Virtue for the Fed

As kids, we were taught that “patience is a virtue.” For the most part, that’s true, as sometimes you must wait for the good things in life.

Yet when it comes to monetary policy, the Federal Reserve now just contradicted this childhood notion of virtue, as the central bank today removed “patient” from its interest rate lexicon. More specifically, in today’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) statement, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and his colleagues retracted its “patient” stance on interest rates and replaced it with “act as appropriate.”

Here’s the money quote from today’s dovish outlook from the FOMC:

“The Committee continues to view sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions and inflation near the Committee’s symmetric two percent objective as the most likely outcomes, but uncertainties about this outlook have increased. In light of these uncertainties and muted inflation pressures, the Committee will closely monitor the implications of incoming information for the economic outlook and will act as appropriate to sustain the expansion, with a strong labor market and inflation near its symmetric two percent objective.”

So, the lesson for kids in this new era of Fed policy might be: “Acting appropriate is a virtue.”

Today, the Fed didn’t actually take much action, as the FOMC left interest rates unchanged at the current federal funds rate between 2.25% and 2.5%. The decision to do so, however, was not unanimous. While nine of 10 members of the rate-setting committee voted to maintain the federal funds rate at current levels, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard dissented, as he wanted to lower rates. Interestingly, this was the first dissenting vote on the FOMC since Powell took the reins at the FOMC in February 2018.

As for markets, basically we got what we expected. I say that, because since the beginning of the month, equities have soared on the growing notion that “patient” would be jettisoned in favor of the first rate cut in years. Yet the market didn’t expect a rate cut today. Rather, the market now is pricing in a 25-basis-point interest rate cut at the July FOMC meeting, and up to three additional rate cuts by the end of the year.

If we step back for a moment to about this time last year, today’s Fed talk seems like a serious flip-flop. Recall that last summer, the market was talking about the economy running too hot and inflation finally blossoming after many years of dormancy. Today, that’s basically an alternate universe.

“This summer, it’s all about trade war instability, potentially slowing job growth, uncertain consumer spending and slowing manufacturing data,” said Tom Essaye of the Sevens Report. “Today, rather than a too-hot economy and rising inflation, markets are expecting — indeed pricing in — one of the most poignant shifts in monetary policy in the last half decade. That shift is the expectation of a new interest-rate cutting cycle by the Federal Reserve,” Tom added.

Tom is hands-down my favorite macro analyst, and he’s usually spot on when it comes to understanding and explaining the wider context of markets. Both Tom and I suspect that we are on the precipice of a new rate cut cycle, one that will have profound implications for investors over the next year or so (depending on duration).

We’re not there yet, but as of this writing, the July Fed Funds Futures contracts are pricing in a 100% probability of a 25-basis-point rate cut at the next FOMC meeting. If that is the first move in a new rate cut cycle, then I will be rotating capital in many of my newsletter advisory services, Successful Investing and Intelligence Report, to take advantage of the sectors that will benefit most from rate cuts. Perhaps more importantly, I will be avoiding the market sectors that have underperformed during past rate cut cycles.

To find out just how I plan to help subscribers navigate this new Fed “impatience,” I invite you to check out my Successful Investing and Intelligence Report advisory services today.

*******************************************************************

It Almost Is Time to Get Buck Wild in Las Vegas!

The time to get intellectually wild is almost here. Yes, I am referring to this year’s FreedomFest conference, and this year’s theme: “The Wild West.”

This conference has been called, “The World’s Largest Gathering of Free Minds,” and for good reason, with more than 2,000 attendees and some 250 speakers and workshops.

I cordially invite you to join me, as well as some of the world’s most renowned and celebrated heroes of the liberty movement such as Penn Jillette, John Mackey, Congressman Justin Amash, Dr. Mark Skousen, Glenn Beck, Charles Murray and scores of others on July 17-20, at the Paris Resort, Las Vegas. Use the promo code EAGLE50 for a special discount offer of $50 off the “Full Conference Pass” price of $595 per person… So that’s $545 per person/$845 per couple.

Come find out how those of us who love liberty celebrate this virtue, and how we get buck wild in Las Vegas!

**************************************************************

ETF Talk: Tap Large-Cap Stocks with This Fund

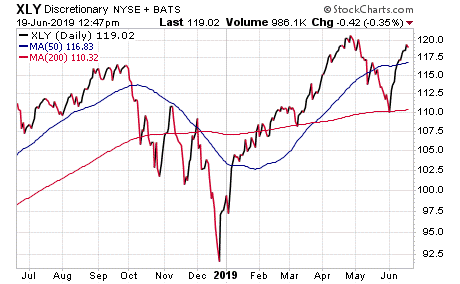

The Consumer Discretionary Select Sector SPDR Fund (XLY) tracks a market-cap-weighted index of consumer-discretionary stocks drawn from the S&P 500.

Consumer discretionary involves goods and services consumers consider to be non-essential, but desirable, if available income allows such purchases. This sector primarily includes industries such as retail, automobiles and components, consumer durables, apparel, hotels and restaurants.

The index includes Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN), Home Depot (NYSE: HD), McDonald’s (NYSE: MCD), Nike (NYSE: NKE) and Ford (NYSE: F). XLY delivers a cheap, liquid portfolio of large-cap consumer-discretionary stocks.

XLY’s basket of stocks is intended to represent the sector well, despite concentration in the largest names. The fund pulls its holdings from the S&P 500, which differs from the broad-market universe used by competing funds, since this one excludes small-caps and most mid-caps. Industry biases are small. Overall, XLY represents the space well at low all-in cost.

Chart courtesy of StockCharts.com

XLY has almost $14 billion in assets under management and an average spread of 0.01%. The fund’s expense ratio of 0.13% ranks among the lowest in the segment, so it is much cheaper to buy compared to other exchange-traded funds. This fund’s trading volume towers over its competitors with an average of more than $483 million.

As for its riskiness, the Consumer Discretionary Select Sector SPDR Fund has an MSCI ESG Fund Rating of BBB, based on a score of 4.45 out of 10. The MSCI ESG Fund Rating measures the resiliency of portfolios to long-term risks and opportunities due to environmental, social and governance factors. ESG Fund Ratings range from best (AAA) to worst (CCC). Top-rated funds buy shares in companies that tend to show strong and/or improving management of financially relevant environmental, social and governance issues.

As always, I am happy to answer any of your questions about ETFs, so do not hesitate to send me an email. You just may see your question answered in a future ETF Talk.

*******************************************************************

In case you missed it…

Breaking Up Is Hard to Do (Another Defense of ‘Economic Bigness’)

What do President Trump and Democratic presidential hopeful Sen. Elizabeth Warren have in common (aside from both wanting to be elected president in 2020)?

The answer is that both have it out for “Big Tech,” and both appear to want to punish companies such as Facebook (FB) and Amazon.com (AMZN) for what essentially amounts to the ostensible “sin” of being too successful and too good at what they do.

President Trump’s opposition to Big Tech isn’t exactly anti-trust based the way it is with Sen. Warren, although it comes close. Rather, the president sees social media sites such as Twitter (TWTR) as “not treating him fairly,” as he told CNBC’s Joe Kernan.

Now, there is no doubt the president is correct if he is saying that social media sites skew to the left ideologically, and that a lot of voices of dissent from the right, or voices that are not politically “woke” about progressive social and racial issues, end up getting banned. That seems to be the fallout from Facebook’s recent crackdown on so-called “extremism” and “misinformation.”

And while not calling for a direct break up of Big Tech, the president seemed to suggest that his administration could go after these companies by using the power of law, and extract fines from them via lawsuits the way the European Union does.

Here’s precisely what the president said in that CNBC interview:

“Every week you see them [the European Union] going after Facebook and Apple and all these companies, that are, you know, great companies but something is going on. But I will say the European Union is suing them all the time. We are going to be looking at them differently. We have a great Attorney General; we are going to look at it differently.

“When they give the European Union $7 billion and $5 billion and $2 billion, and you know, Apple gets sued for $10 billion. And you know, right now, it is going on, but they’ll end up settling. They get all this money. We should be doing that — they’re our companies, so they’re actually attacking our companies. But we should be doing what they’re doing.”

So, there you have it, the President of the United States is saying that America should use the long arm of the law to punish and fine Big Tech the way EU regulators are doing, because by doing so the government will be able to get money out of them. Sort of like milking a cash cow via the threat of government force.

Now, when it comes to Sen. Warren, she straight up thinks these companies are too big (i.e. too profitable) to escape the vice grip of her socialistic idea of corporate governance. Here’s Sen. Warren in her own words, accusing Big Tech of being too successful, having too much power, and in need of her remedy for their economic bigness.

“Today’s big tech companies have too much power — too much power over our economy, our society and our democracy,” Sen. Warren said. “They’ve bulldozed competition, used our private information for profit and tilted the playing field against everyone else. And in the process, they have hurt small businesses and stifled innovation… That’s why my administration will make big, structural changes to the tech sector to promote more competition — including breaking up Amazon, Facebook and Google.”

Forget for a moment how inaccurate Warren’s claims are about these companies hurting small business and stifling innovation. She just can’t stand the idea that there are some companies that appear to be more “powerful” than Big Government.

So, what we have here is the president, who wants to punish Big Tech via its pocketbook (take that, shareholders!) while Sen. Warren wants to tell each of the companies how they have to run their businesses, how big they can get, what decisions they can make, etc. Because after all, Sen. Warren knows how to run these businesses better than Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg and Sundar Pichai.

This whole notion of having the government tell these companies what to do, and/or fining them because they are acting “unfair,” according to politicians, is outrageous. It also is an abrogation of the principle of freedom the country was founded on.

Now, in November, I wrote a column here in The Deep Woods titled, “In Defense of Economic Bigness.” In that column, I took on an idea promulgated by Columbia University law professor Tim Wu, who claims that the problem of “Economic Bigness” can lead to a rise in fascism such as we saw in 1930’s Germany. And no, I am not making this stuff up!

I want to repost that piece here today, as it’s a good way to address the prevailing zeitgeist among both sides of the political aisle that want to unleash the wrath of government on companies that became big only because nearly all of us want to use their respective products. Keep that in mind when you read this, and when anyone tells you that Big Tech needs to be punished for the “sin” of being too successful.

(The following was originally published on Nov. 14, 2018.)

In Defense of Economic ‘Bigness’

There’s an op-ed in the New York Times that has been getting some buzz over the past few days. It is written by Tim Wu, a law professor at Columbia University, one of the most outspoken advocates for harsher and more intrusive antitrust laws.

In his latest piece, “Be Afraid of Economic ‘Bigness.’ Be Very Afraid,” Wu makes the argument that monopoly and excessive corporate concentration can lead to what Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis once called the “curse of bigness.” Wu also argues that this “bigness” was a key component that led to the rise of Hitler, and that it was part of the economic origins of fascism.

What is that they say about an argument… if you have to resort to a Hitler reference, you’ve already lost?

Now, I don’t quite view Professor Wu’s argument in such simplistic terms. I do, however, think it ironic that fascism — which is just another form of big-government collectivism where the state is in control of the economy — is somehow the result of big business.

To be fair, Wu says it was the German economic structure, which was dominated by monopolies and cartels, that was essential to Hitler’s consolidation of power. And while it’s true that dictators throughout history nationalized industries and businesses under the threat of violence for their own nefarious purposes, it seems to me that blaming “big” industries for those nefarious purposes is a woefully misguided case of putting the cart before the horse.

But Wu doesn’t stop with just a look back at Nazi Germany. Instead, he applies the fear of bigness to what’s going on in the economy now, and particularly in places such as Silicon Valley, to argue that we need more invasive government and more antitrust law enforcement to rein in the bigness.

Here’s Wu’s basic thesis, in his own words:

“There are many differences between the situation in 1930s and our predicament today. But given what we know, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that we are conducting a dangerous economic and political experiment: We have chosen to weaken the laws — the antitrust laws — that are meant to resist the concentration of economic power in the United States and around the world.”

But are antitrust laws really designed to resist economic concentration of power, or are they more like legal means to give the government more power over a free society?

According to novelist/philosopher and free-market champion Ayn Rand, antitrust laws were “allegedly created to protect competition.” Yet Rand argued that these laws were based on the “socialistic fallacy” that a free market will inevitably lead to the establishment of coercive monopolies. She further argued that it was government that was the cause of monopolies, not free markets.

As Rand wrote, “Every coercive monopoly was created by government intervention into the economy: by special privileges, such as franchises or subsidies, which closed the entry of competitors into a given field, by legislative action… The antitrust laws were the classic example of a moral inversion prevalent in the history of capitalism: an example of the victims, the businessmen, taking the blame for the evils caused by the government, and the government using its own guilt as a justification for acquiring wider powers, on the pretext of ‘correcting’ the evils.”

Well, Wu certainly wants to correct what he sees as these evils, and he wants the government to do so much more than it has been doing.

“In recent years, we have allowed unhealthy consolidations of hospitals and the pharmaceutical industry; accepted an extraordinarily concentrated banking industry, despite its repeated misfeasance; failed to prevent firms like Facebook from buying up their most effective competitors; allowed AT&T to reconsolidate after a well-deserved breakup in the 1980s; and the list goes on,” writes Wu.

Note the term “we have allowed,” as if government was the moral arbiter of one group of individuals and the free exchange of ideas, capital and cooperation with another group.

Wu even doubled down on the Facebook (FB) and Silicon Valley consolidation trends in an interview with CNBC, saying, “I think it could be very important, for example, to take action against Facebook to break up some of their illegal mergers, especially Instagram and WhatsApp, to kind of recharge the innovation environment.”

Recharge the innovation environment? Really?

I don’t know if Mr. Wu has visited Silicon Valley lately, but I can assure him that there is no shortage of innovation among tech startups. In fact, many are those startups would love to be acquired by the likes of Facebook or Alphabet or Apple or any number of bigger suiters.

Oh, and who wins from such mergers? Well, it’s usually customers who get convenient access to better products, and shareholders of firms that are monetizing these acquisitions. Facebook, for example, has seen its share price surge some 200% over the past five years. And while it’s not always the case that consumers or shareholders win when an industry consolidates, it usually always is the case that consumers lose when big government comes in and dictates the winners and losers.

Now, this is The Deep Woods, and in this e-letter, we dig into the deeper principles of an issue. Here, the principle involved is the proper jurisdiction over free peoples.

By what right, I ask you, does the government claim to legislate the free actions of individuals that make up corporations and companies?

These entities are freely associating with others, and using capital to make sound business decisions such as acquisitions, mergers, etc. We must assume here that these individuals are acting in what they consider to be their own mutual best interests, even if those choices ultimately turn out to be wrong.

The answer, of course, is the government has no right, and these companies are violating no laws. So, the government had to make up a new right, and that’s what they call antitrust laws.

Finally, the only real danger in the history of humanity from “bigness” is the rise of big government, i.e. the rise to power of those who wield the swords, guns and missiles — and, of course, the big laws they have restricting the freedom of citizens.

*********************************************************************

Always Trust Your Cape

Old and grey with a flour sack cape tied all around his head

He’s still jumpin’ off the garage, will be till he’s dead

All these years the people said he’s actin’ like a kid

He did not know he could not fly, so he did

Well he’s one of those who knows that life is just a leap of faith

Spread your arms and hold your breath, and always trust your cape

— Guy Clark, “The Cape”

The late Guy Clark is a Texas songwriting legend, and he also happens to have written one of my favorite tunes, “The Cape.” I love it, because it tells the tale of a free-spirited boy, then a man, then an elder gentleman, who keeps pushing the limits in life despite the naysayers. My favorite lyric in the song is, “He did not know he could not fly, so he did.” The moral of this song is to forget about your limitations and just go for it. Or more poetically, to spread your arms and hold your breath — and always trust your cape.

Wisdom about money, investing and life can be found anywhere. If you have a good quote that you’d like me to share with your fellow readers, send it to me, along with any comments, questions and suggestions you have about my newsletters, seminars or anything else. Click here to ask Jim.

In the name of the best within us,

Jim Woods